Gerardi Ernst

初级会员

維吾爾族及其他穆斯林遭不公重判

Click to expand Image

A perimeter fence around what is officially known as a” vocational skills education center” in Dabancheng in China's Xinjiang region, September 2018. © 2018 Reuters/Thomas Peter

(紐約)- 人權觀察今天表示,中國政府近年來在新疆地區對維吾爾族及其他穆斯林無故起訴並判處重刑的案件增加。從2016年中國政府加大力度推行鎮壓式的「嚴厲打擊暴力恐怖活動專項行動」迄今,該地區已有逾25萬人遭正式司法系統定罪判刑。

由於新疆當局嚴密管制資訊,僅有極少數判決書和官方文件能夠公開取得,人權觀察分析其中近60宗案件發現,許多人並未犯罪卻遭判刑入獄。除了這些正式起訴的案件之外,還有許多人被任意拘禁在非法的「政治教育」設施。

「中國政府開設『政治教育』營的作法已引起國際公憤,但新疆穆斯林遭正式司法系統逮捕拘禁的情況卻未得到太多關注,」人權觀察中國部高級研究員王松蓮說。「儘管表面看來合法,其實新疆監獄中許多囚犯只不過是為了正常營生和踐行宗教信仰而被定罪。」

刑控激增,大量重刑

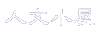

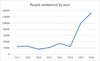

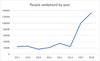

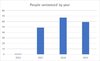

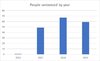

如非政府組織中國人權捍衛者網絡(CHRD)及《紐約時報》2019年所報導,中國官方統計顯示,新疆判刑人數於2017年驟然上升,並在2018年繼續增加。

Click to expand Image

Source: China Law Yearbooks, Xinjiang Regional Yearbooks and Xinjiang Court Annual Work Reports

根據中國官方統計,新疆各法院在2017年合計判刑99,326人,2018年為133,198人。當局未公布2019年判刑數據。

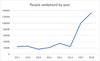

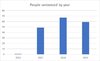

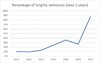

《新疆受害者資料庫》——根據家屬陳述和官方文件紀錄逾8千名囚犯資料的非政府組織——估計2019年的判刑人數應與前兩年相當。在178宗判刑年度已知的案件當中,2019年被判刑的人數大致符合2017到2018年的平均數。

Click to expand Image

Source: Xinjiang Victims Database

官方判刑數目相當,可能代表2019年在新疆被判刑的人數高達數萬以上。

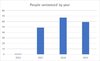

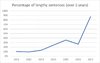

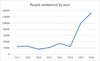

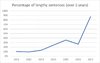

2017年的另一個改變是被判重刑的人數大幅增加,如官方統計所示。2017年之前,判刑超過五年的人數佔所有判刑人數的百分之10.8。同一比率在2017年突然升高到百分之87。

Click to expand Image

Source: Xinjiang Regional Yearbooks

《新疆受害者資料庫》也顯示,在刑期已知的312人當中,在「嚴打行動」期間判刑者的平均刑度是12.5年,其中包括六人被判處無期徒刑。

嚴打期間任意監禁

金懷德的案件生動呈現新疆大規模監禁穆斯林的任意性質。2018年9月,這位回族穆斯林在昌吉縣以「分裂國家罪」被判處終身監禁。根據人權觀察取得的該案判決書,昌吉縣中級人民法院認定47歲的金懷德「反復非法」組織海外古蘭經研習活動,邀請孟加拉和吉爾吉斯等國宗教人士訪問新疆,並於2006到2014年之間多次在新疆舉辦宗教討論活動。當局指控金懷德鼓勵其他人參加伊斯蘭傳道會(Tablighi Jamaat),一種跨國伊斯蘭宣教運動。

並無任何公開可得的證據足以證明金懷德的行為構成公認的刑事犯罪。但法院仍認定他的活動「有助促進外國宗教勢力滲透中國」、「強化伊斯蘭教將統一全世界,最終建立哈里發政權的思想」並且因此「危害國家」。

金懷德曾因同樣行為於2015年以「聚眾擾亂社會秩序罪」被判刑七年,但人民檢察院於2017年上訴請求加重刑罰,再審後改判無期徒刑。在此案之前,金懷德曾因向20餘名回族與維吾爾族兒童講授古蘭經,於2009年被判刑18個月。

除金懷德案以外,《新疆受害者資料庫》還發現其他六宗案件,部分資料來自當事人家屬:

其中一份文件是逮捕維吾爾族一家四人的起訴書,顯示中國政府如何惡意擴大濫用「恐怖主義」和「極端主義」概念。這四人因曾在2013到2014年前往土耳其探親而於2019年1月被起訴。中國當局指稱他們到土耳其會見的對象——大學教師艾爾金・艾買提(Erkin Emet)——是恐怖組織成員,而他們帶去給他的金錢(約2,500美元)和禮品——包括一把都塔爾琴(傳統樂器)、一枚金戒指和若干必需品——是「幫助恐怖活動」的物證。據艾買提表示,他在2019年得知其家屬四人以及另一名表親分別被判處11年到23年不等徒刑。

由上述各項判決以及其他案件訊息可知,新疆各地法院將許多無辜者定罪判刑。

嚴打行動缺乏正當程序

新疆「嚴厲打擊暴力恐怖活動專項行動」的目標是突厥裔穆斯林的「思想病毒」,即不受國家許可的宗教與政治觀點,例如泛伊斯蘭主義。該行動並包括對全區民眾進行大規模監控和政治思想灌輸。當局以無理、空泛的標準——例如是否有海外親屬——決定「矯正」方式。當局認定違犯情節較輕微的,就送進政治教育營或以其他形式限制行動,包括軟禁。由政府過去作法來看,情節較嚴重的便會交由正式的刑事司法系統處理。

「嚴打」是中國當局每隔一段時間就會發動的典型「打擊犯罪」政治運動。當局要求公安、檢察與法院合力實施迅速、嚴厲的懲處,以即審即決方式在短時間內處理大量案件,排除中國法律保障的基本程序權利。

新疆的「嚴打」也是如此。許多新聞報導描述,包括刑事司法系統在內的新疆政府官員均承受龐大工作壓力。有一則報導說,公檢法官員忙到沒空吃飯、睡覺,假期也都取消。人權觀察2018年訪談曾於2016到2018年被羈押在新疆看守所的人士說,他們和其他在押人員都曾遭刑訊逼供,而且不准聯絡律師。自由亞洲電台報導,眾多人員經過連家屬也無法旁聽的秘密審判即被草率判刑。

國際壓力可能有助促使中國政府釋放部分「政治教育」營在押人員。中國政府否認在新疆實施大規模任意拘禁,聲稱「依法治疆」。但許多人被強迫失蹤,在家屬完全未被通知之下遭到拘留或監禁。獲釋人員也持續受到監控、限制遷徙,有些人則被強迫勞動。

「國際社會必須升高對中國政府的壓力,要求對新疆情勢進行獨立調查,」王松蓮說。「唯有如此才可能促使所有被不當拘押或監禁的人們獲得釋放。」

英文版如下:

China: Baseless Imprisonments Surge in Xinjiang

Harsh, Unjust Sentences for Uyghurs, Other Muslims

Click to expand Image

A perimeter fence around what is officially known as a” vocational skills education center” in Dabancheng in China's Xinjiang region, September 2018. © 2018 Reuters/Thomas Peter

(New York) – The Chinese government has increased its groundless prosecutions with long prison sentences for Uyghurs and other Muslims in recent years in China’s Xinjiang region, Human Rights Watch said today. Since the Chinese government escalated its repressive “Strike Hard Campaign against Violent Terrorism” in late 2016, the region’s formal criminal justice system has convicted and sentenced more than 250,000 people.

While few verdicts and other official documents are publicly available due to Xinjiang authorities’ tight control of information, a Human Rights Watch analysis of nearly 60 of these cases suggests that many people have been convicted and imprisoned without committing a genuine offense. These formal prosecutions are distinct from those arbitrarily detained in unlawful “political education” facilities.

“Although the Chinese government’s use of ‘political education’ camps has led to international outrage, the detention and imprisonment of Xinjiang’s Muslims by the formal justice system has attracted far less attention,” said Maya Wang, senior China researcher. “Despite the veneer of legality, many of those in Xinjiang’s prisons are ordinary people who were convicted for going about their lives and practicing their religion.”

Prosecutions Increase Sharply, Many for Long Sentences

The Chinese government’s official statistics showed a dramatic increase in the number of people sentenced in Xinjiang in 2017, followed by another increase in 2018, as reported by the nongovernmental organization, Network of Chinese Human Rights Defenders, and the New York Timesin 2019.

Click to expand Image

Source: China Law Yearbooks, Xinjiang Regional Yearbooks and Xinjiang Court Annual Work Reports

According to Chinese government statistics, Xinjiang courts sentenced 99,326 people in 2017 and 133,198 in 2018. The authorities have not released sentencing statistics for 2019.

The Xinjiang Victims Database – a nongovernmental organization that has documented the cases of over 8,000 detainees based on family accounts and official documents – estimates that the number of people sentenced in 2019 may be comparable to those in the previous two years. Of the 178 cases whose year of sentencing is known, the number of people sentenced in 2019 is roughly the average of those of 2017 and 2018.

Click to expand Image

Source: Xinjiang Victims Database

A comparable official sentencing figure could mean that tens of thousands more people were sentenced in Xinjiang in 2019.

Another change in 2017 was the dramatic increase in the number of those given lengthy sentences, also according to government statistics. Prior to 2017, sentences of over five years in prison were about 10.8 percent of the total number of people sentenced. In 2017, they make up 87 percent of the sentences.

Click to expand Image

Source: Xinjiang Regional Yearbooks

Similarly, the dataset from the Xinjiang Victims Database shows that among the 312 individuals whose prison terms are known, people are being imprisoned for, on average, 12.5 years during the Strike Hard Campaign. That figure excludes six people who have been given life sentences.

Arbitrary Imprisonments Under the Strike Hard Campaign

One case that vividly illustrates the arbitrary nature of Xinjiang’s mass imprisonment of Muslims is that of Jin Dehuai, a Hui Muslim sentenced to life imprisonment for “splittism” in Changji Prefecture in September 2018. In a verdict obtained by Human Rights Watch, the Changji Intermediate People’s Court convicted Jin, 47, for “repeatedly and illegally” organizing trips abroad to study the Quran, inviting religious figures from countries including Bangladesh and Kyrgyzstan to Xinjiang, and holding religious meetings in the region between 2006 and 2014. The authorities accused Jin of encouraging others to take part in Tablighi Jamaat, a kind of transnational movement of Islamic proselytization.

There is no publicly available evidence that Jin’s activities constituted a recognizable criminal offense. Yet the court determined that his activities had “promoted the infiltration of foreign religious forces in China,” “strengthened the idea that Islam will unite the world, ultimately to establish a caliphate,” and thus “endangered the country.”

Jin was sentenced to seven years for “gathering crowds to disturb social order” in 2015 for these same behaviors, but the procuratorate challenged the verdict in 2017 and asked for a heavier sentence, resulting in a retrial that resulted in a life sentence. Prior to this sentence, in 2009, Jin had been imprisoned for 18 months for teaching the Quran to over two dozen Hui and Uyghur children.

Aside from Jin Huaide’s case, the Xinjiang Victims Database found six others, some provided by families:

One such document, an indictment detaining the case of four Uyghur family members, illustrates the Chinese government’s perilously over-expansive use of the terms “terrorism” and “extremism.” The four were indicted in January 2019 for travelling to Turkey in 2013 and 2014 to visit another family member. Chinese authorities claimed that the man in Turkey, a university lecturer named Erkin Emet, belongs to a terrorist organization, and that the money (US$2,500) and gifts his family gave him – including a dutar, a traditional musical instrument, a gold ring, and basic necessities – were evidence of them “assisting terrorism.” These four, along with another sibling of Emet, were given sentences of 11 to 23 years, according to Emet, who in 2019 learned about their conviction.

These verdicts and the additional case information suggest that the courts in Xinjiang have convicted and imprisoned many people who had not committed a genuine offense.

No Due Process Under Strike Hard Campaign

Xinjiang’s Strike Hard Campaign targets the “ideological virus” of Turkic Muslims, religious and political ideas that do not conform to those prescribed by the state, such as pan-Islamism. It involves mass surveillance and political indoctrination of the entire population. The authorities evaluate people’s thoughts, behavior, and relationships based on bogus and broad criteria – such as whether they have families abroad – to determine their course of “correction.” Those whose transgressions the authorities consider light are held in political education camps or under other forms of movement restrictions, including house arrest. Past government practice suggests that more serious cases are processed in the formal criminal justice system.

The Strike Hard Campaign is typical of Chinese authorities’ periodic and politicized “anti-crime” initiatives. The authorities pressure the police, procuratorate, and courts to cooperate to deliver swift and harsh punishment, leading to summary trials, the processing of large number of cases in a short time, and a suspension of basic procedural rights under Chinese law.

Similar dynamics appear to characterize Xinjiang’s Strike Hard Campaign. News reports describe crushing work pressure on Xinjiang officials, including those in the criminal justice system. One describes police officers, procurators, and judges not having time to eat or sleep, and holidays being suspended. Human Rights Watch in 2018 interviewed people held in Xinjiang’s formal detention centers between 2016 and 2018 who said that they and fellow detainees were tortured to confess crimes and deprived of access to lawyers. Radio Free Asia has reported that people are being sentenced with perfunctory and closed trials that families cannot attend.

International pressure may have contributed to the Chinese government releasing some detainees from “political education” camps. The government, which has denied mass arbitrary detentions in Xinjiang, has asserted that it governs the region according to the “rule of law.” But many people have been forcibly disappeared, detained or imprisoned with their families not informed of their whereabouts. Those released are subjected to continued surveillance, control of their movements, and some to forced labor.

“International pressure on the Chinese government should be escalated for an independent investigation in Xinjiang,” Wang said. “That’s the best hope for the release of all those unjustly detained or imprisoned.”

Click to expand Image

A perimeter fence around what is officially known as a” vocational skills education center” in Dabancheng in China's Xinjiang region, September 2018. © 2018 Reuters/Thomas Peter

(紐約)- 人權觀察今天表示,中國政府近年來在新疆地區對維吾爾族及其他穆斯林無故起訴並判處重刑的案件增加。從2016年中國政府加大力度推行鎮壓式的「嚴厲打擊暴力恐怖活動專項行動」迄今,該地區已有逾25萬人遭正式司法系統定罪判刑。

由於新疆當局嚴密管制資訊,僅有極少數判決書和官方文件能夠公開取得,人權觀察分析其中近60宗案件發現,許多人並未犯罪卻遭判刑入獄。除了這些正式起訴的案件之外,還有許多人被任意拘禁在非法的「政治教育」設施。

「中國政府開設『政治教育』營的作法已引起國際公憤,但新疆穆斯林遭正式司法系統逮捕拘禁的情況卻未得到太多關注,」人權觀察中國部高級研究員王松蓮說。「儘管表面看來合法,其實新疆監獄中許多囚犯只不過是為了正常營生和踐行宗教信仰而被定罪。」

刑控激增,大量重刑

如非政府組織中國人權捍衛者網絡(CHRD)及《紐約時報》2019年所報導,中國官方統計顯示,新疆判刑人數於2017年驟然上升,並在2018年繼續增加。

Click to expand Image

Source: China Law Yearbooks, Xinjiang Regional Yearbooks and Xinjiang Court Annual Work Reports

根據中國官方統計,新疆各法院在2017年合計判刑99,326人,2018年為133,198人。當局未公布2019年判刑數據。

《新疆受害者資料庫》——根據家屬陳述和官方文件紀錄逾8千名囚犯資料的非政府組織——估計2019年的判刑人數應與前兩年相當。在178宗判刑年度已知的案件當中,2019年被判刑的人數大致符合2017到2018年的平均數。

Click to expand Image

Source: Xinjiang Victims Database

官方判刑數目相當,可能代表2019年在新疆被判刑的人數高達數萬以上。

2017年的另一個改變是被判重刑的人數大幅增加,如官方統計所示。2017年之前,判刑超過五年的人數佔所有判刑人數的百分之10.8。同一比率在2017年突然升高到百分之87。

Click to expand Image

Source: Xinjiang Regional Yearbooks

《新疆受害者資料庫》也顯示,在刑期已知的312人當中,在「嚴打行動」期間判刑者的平均刑度是12.5年,其中包括六人被判處無期徒刑。

嚴打期間任意監禁

金懷德的案件生動呈現新疆大規模監禁穆斯林的任意性質。2018年9月,這位回族穆斯林在昌吉縣以「分裂國家罪」被判處終身監禁。根據人權觀察取得的該案判決書,昌吉縣中級人民法院認定47歲的金懷德「反復非法」組織海外古蘭經研習活動,邀請孟加拉和吉爾吉斯等國宗教人士訪問新疆,並於2006到2014年之間多次在新疆舉辦宗教討論活動。當局指控金懷德鼓勵其他人參加伊斯蘭傳道會(Tablighi Jamaat),一種跨國伊斯蘭宣教運動。

並無任何公開可得的證據足以證明金懷德的行為構成公認的刑事犯罪。但法院仍認定他的活動「有助促進外國宗教勢力滲透中國」、「強化伊斯蘭教將統一全世界,最終建立哈里發政權的思想」並且因此「危害國家」。

金懷德曾因同樣行為於2015年以「聚眾擾亂社會秩序罪」被判刑七年,但人民檢察院於2017年上訴請求加重刑罰,再審後改判無期徒刑。在此案之前,金懷德曾因向20餘名回族與維吾爾族兒童講授古蘭經,於2009年被判刑18個月。

除金懷德案以外,《新疆受害者資料庫》還發現其他六宗案件,部分資料來自當事人家屬:

- 乃比江・吾加・艾合買提,維吾爾族,因向人解說「何謂禁忌與合法」(伊斯蘭教戒律)被控「煽動民族仇恨與歧視」判刑10年;

- 黃世科,回族,因在兩個微信群組中解說古蘭經被控「非法利用信息網絡罪」判刑二年;

- 阿斯哈・阿孜提別克,哈薩克族,因帶領來訪的哈薩克官員參觀中哈邊境水利工程,被控「間諜罪」與「詐騙罪」,判刑20年;

- 聶世崗,回族,因協助逾百名維吾爾族人匯款給旅居埃及親屬,被當局認定為恐怖活動資金,原被控「幫助恐怖活動罪」和「洗錢罪」判刑15年。上訴後,法院認定聶某不構成「幫助恐怖活動罪」,僅犯「洗錢罪」,並將刑期減為五年;

- 努爾蘭・皮吾尼爾,哈薩克族,因在新疆為70多人提供宗教教育被控「擾亂公共秩序罪」、「宣揚極端主義罪」,判刑17年;

- 塞力克江・阿德勒汗,哈薩克族,因私自銷售價值人民幣174,600元(約27,000美元)的香菸被控「非法經營罪」判刑三年半。塞力克江・阿德勒汗的判決書是中國官方裁判文書資料庫公布的僅有七份法庭判決之一。

其中一份文件是逮捕維吾爾族一家四人的起訴書,顯示中國政府如何惡意擴大濫用「恐怖主義」和「極端主義」概念。這四人因曾在2013到2014年前往土耳其探親而於2019年1月被起訴。中國當局指稱他們到土耳其會見的對象——大學教師艾爾金・艾買提(Erkin Emet)——是恐怖組織成員,而他們帶去給他的金錢(約2,500美元)和禮品——包括一把都塔爾琴(傳統樂器)、一枚金戒指和若干必需品——是「幫助恐怖活動」的物證。據艾買提表示,他在2019年得知其家屬四人以及另一名表親分別被判處11年到23年不等徒刑。

由上述各項判決以及其他案件訊息可知,新疆各地法院將許多無辜者定罪判刑。

嚴打行動缺乏正當程序

新疆「嚴厲打擊暴力恐怖活動專項行動」的目標是突厥裔穆斯林的「思想病毒」,即不受國家許可的宗教與政治觀點,例如泛伊斯蘭主義。該行動並包括對全區民眾進行大規模監控和政治思想灌輸。當局以無理、空泛的標準——例如是否有海外親屬——決定「矯正」方式。當局認定違犯情節較輕微的,就送進政治教育營或以其他形式限制行動,包括軟禁。由政府過去作法來看,情節較嚴重的便會交由正式的刑事司法系統處理。

「嚴打」是中國當局每隔一段時間就會發動的典型「打擊犯罪」政治運動。當局要求公安、檢察與法院合力實施迅速、嚴厲的懲處,以即審即決方式在短時間內處理大量案件,排除中國法律保障的基本程序權利。

新疆的「嚴打」也是如此。許多新聞報導描述,包括刑事司法系統在內的新疆政府官員均承受龐大工作壓力。有一則報導說,公檢法官員忙到沒空吃飯、睡覺,假期也都取消。人權觀察2018年訪談曾於2016到2018年被羈押在新疆看守所的人士說,他們和其他在押人員都曾遭刑訊逼供,而且不准聯絡律師。自由亞洲電台報導,眾多人員經過連家屬也無法旁聽的秘密審判即被草率判刑。

國際壓力可能有助促使中國政府釋放部分「政治教育」營在押人員。中國政府否認在新疆實施大規模任意拘禁,聲稱「依法治疆」。但許多人被強迫失蹤,在家屬完全未被通知之下遭到拘留或監禁。獲釋人員也持續受到監控、限制遷徙,有些人則被強迫勞動。

「國際社會必須升高對中國政府的壓力,要求對新疆情勢進行獨立調查,」王松蓮說。「唯有如此才可能促使所有被不當拘押或監禁的人們獲得釋放。」

英文版如下:

China: Baseless Imprisonments Surge in Xinjiang

Harsh, Unjust Sentences for Uyghurs, Other Muslims

Click to expand Image

A perimeter fence around what is officially known as a” vocational skills education center” in Dabancheng in China's Xinjiang region, September 2018. © 2018 Reuters/Thomas Peter

(New York) – The Chinese government has increased its groundless prosecutions with long prison sentences for Uyghurs and other Muslims in recent years in China’s Xinjiang region, Human Rights Watch said today. Since the Chinese government escalated its repressive “Strike Hard Campaign against Violent Terrorism” in late 2016, the region’s formal criminal justice system has convicted and sentenced more than 250,000 people.

While few verdicts and other official documents are publicly available due to Xinjiang authorities’ tight control of information, a Human Rights Watch analysis of nearly 60 of these cases suggests that many people have been convicted and imprisoned without committing a genuine offense. These formal prosecutions are distinct from those arbitrarily detained in unlawful “political education” facilities.

“Although the Chinese government’s use of ‘political education’ camps has led to international outrage, the detention and imprisonment of Xinjiang’s Muslims by the formal justice system has attracted far less attention,” said Maya Wang, senior China researcher. “Despite the veneer of legality, many of those in Xinjiang’s prisons are ordinary people who were convicted for going about their lives and practicing their religion.”

Prosecutions Increase Sharply, Many for Long Sentences

The Chinese government’s official statistics showed a dramatic increase in the number of people sentenced in Xinjiang in 2017, followed by another increase in 2018, as reported by the nongovernmental organization, Network of Chinese Human Rights Defenders, and the New York Timesin 2019.

Click to expand Image

Source: China Law Yearbooks, Xinjiang Regional Yearbooks and Xinjiang Court Annual Work Reports

According to Chinese government statistics, Xinjiang courts sentenced 99,326 people in 2017 and 133,198 in 2018. The authorities have not released sentencing statistics for 2019.

The Xinjiang Victims Database – a nongovernmental organization that has documented the cases of over 8,000 detainees based on family accounts and official documents – estimates that the number of people sentenced in 2019 may be comparable to those in the previous two years. Of the 178 cases whose year of sentencing is known, the number of people sentenced in 2019 is roughly the average of those of 2017 and 2018.

Click to expand Image

Source: Xinjiang Victims Database

A comparable official sentencing figure could mean that tens of thousands more people were sentenced in Xinjiang in 2019.

Another change in 2017 was the dramatic increase in the number of those given lengthy sentences, also according to government statistics. Prior to 2017, sentences of over five years in prison were about 10.8 percent of the total number of people sentenced. In 2017, they make up 87 percent of the sentences.

Click to expand Image

Source: Xinjiang Regional Yearbooks

Similarly, the dataset from the Xinjiang Victims Database shows that among the 312 individuals whose prison terms are known, people are being imprisoned for, on average, 12.5 years during the Strike Hard Campaign. That figure excludes six people who have been given life sentences.

Arbitrary Imprisonments Under the Strike Hard Campaign

One case that vividly illustrates the arbitrary nature of Xinjiang’s mass imprisonment of Muslims is that of Jin Dehuai, a Hui Muslim sentenced to life imprisonment for “splittism” in Changji Prefecture in September 2018. In a verdict obtained by Human Rights Watch, the Changji Intermediate People’s Court convicted Jin, 47, for “repeatedly and illegally” organizing trips abroad to study the Quran, inviting religious figures from countries including Bangladesh and Kyrgyzstan to Xinjiang, and holding religious meetings in the region between 2006 and 2014. The authorities accused Jin of encouraging others to take part in Tablighi Jamaat, a kind of transnational movement of Islamic proselytization.

There is no publicly available evidence that Jin’s activities constituted a recognizable criminal offense. Yet the court determined that his activities had “promoted the infiltration of foreign religious forces in China,” “strengthened the idea that Islam will unite the world, ultimately to establish a caliphate,” and thus “endangered the country.”

Jin was sentenced to seven years for “gathering crowds to disturb social order” in 2015 for these same behaviors, but the procuratorate challenged the verdict in 2017 and asked for a heavier sentence, resulting in a retrial that resulted in a life sentence. Prior to this sentence, in 2009, Jin had been imprisoned for 18 months for teaching the Quran to over two dozen Hui and Uyghur children.

Aside from Jin Huaide’s case, the Xinjiang Victims Database found six others, some provided by families:

- Nebijan Ghoja Ehmet, an ethnic Uyghur, was convicted of “inciting ethnic hatred and discrimination” for telling others “what is haram and halal” (prohibited and permissible in Islam) and sentenced to 10 years in prison;

- Huang Shike, Hui, was convicted of “illegal use of the internet” for explaining the Quran to others in two WeChat groups and sentenced to two years in prison;

- Asqar Azatbek, Kazakh, was convicted of “spying and fraud” for showing a visiting Kazakh official around hydraulic projects near the Kazakh-Chinese border and sentenced to 20 years in prison;

- Nie Shigang, Hui, was originally convicted of “assisting in terrorist activities” and “money laundering” for helping over 100 Uyghurs transfer money to their relatives in Egypt – funds authorities said were used for terrorist activities – and sentenced to 15 years in prison. Upon appeal, however, the court ruled that Nie was not guilty of “assisting in terrorist activities” and reduced his sentence to five years for “money laundering;”

- Nurlan Pioner, Kazakh, was convicted of “disturbing public order and extremism” for educating over 70 people in religion, and sentenced to 17 years in prison;

- Serikzhan Adilhan, Kazakh, was convicted of running an “illegal business” for selling cigarettes worth 174,600 RMB (US$27,000) without a license and sentenced to 3 and a half years. The verdict of Serikzhan Adilhan is the only one of the seven available verdicts that is posted on China’s official database of court verdicts.

One such document, an indictment detaining the case of four Uyghur family members, illustrates the Chinese government’s perilously over-expansive use of the terms “terrorism” and “extremism.” The four were indicted in January 2019 for travelling to Turkey in 2013 and 2014 to visit another family member. Chinese authorities claimed that the man in Turkey, a university lecturer named Erkin Emet, belongs to a terrorist organization, and that the money (US$2,500) and gifts his family gave him – including a dutar, a traditional musical instrument, a gold ring, and basic necessities – were evidence of them “assisting terrorism.” These four, along with another sibling of Emet, were given sentences of 11 to 23 years, according to Emet, who in 2019 learned about their conviction.

These verdicts and the additional case information suggest that the courts in Xinjiang have convicted and imprisoned many people who had not committed a genuine offense.

No Due Process Under Strike Hard Campaign

Xinjiang’s Strike Hard Campaign targets the “ideological virus” of Turkic Muslims, religious and political ideas that do not conform to those prescribed by the state, such as pan-Islamism. It involves mass surveillance and political indoctrination of the entire population. The authorities evaluate people’s thoughts, behavior, and relationships based on bogus and broad criteria – such as whether they have families abroad – to determine their course of “correction.” Those whose transgressions the authorities consider light are held in political education camps or under other forms of movement restrictions, including house arrest. Past government practice suggests that more serious cases are processed in the formal criminal justice system.

The Strike Hard Campaign is typical of Chinese authorities’ periodic and politicized “anti-crime” initiatives. The authorities pressure the police, procuratorate, and courts to cooperate to deliver swift and harsh punishment, leading to summary trials, the processing of large number of cases in a short time, and a suspension of basic procedural rights under Chinese law.

Similar dynamics appear to characterize Xinjiang’s Strike Hard Campaign. News reports describe crushing work pressure on Xinjiang officials, including those in the criminal justice system. One describes police officers, procurators, and judges not having time to eat or sleep, and holidays being suspended. Human Rights Watch in 2018 interviewed people held in Xinjiang’s formal detention centers between 2016 and 2018 who said that they and fellow detainees were tortured to confess crimes and deprived of access to lawyers. Radio Free Asia has reported that people are being sentenced with perfunctory and closed trials that families cannot attend.

International pressure may have contributed to the Chinese government releasing some detainees from “political education” camps. The government, which has denied mass arbitrary detentions in Xinjiang, has asserted that it governs the region according to the “rule of law.” But many people have been forcibly disappeared, detained or imprisoned with their families not informed of their whereabouts. Those released are subjected to continued surveillance, control of their movements, and some to forced labor.

“International pressure on the Chinese government should be escalated for an independent investigation in Xinjiang,” Wang said. “That’s the best hope for the release of all those unjustly detained or imprisoned.”